In this blend of documentary and fiction, a writer follows his bloody family history back to the Peruvian land his grandfather exploited for profit.

The Gold Machine (2022) is a dense documentary. Featuring an aging man’s poetic musings on his colonial ancestry and historical, geographical and sociological factual content, it demands attention. Writer Iain Sinclair worked on the documentary alongside director Grant Gee to adapt his 2021 book of the same name, which explores the legacy of his great-grandfather Arthur Sinclair by retracing his journey in Peru.

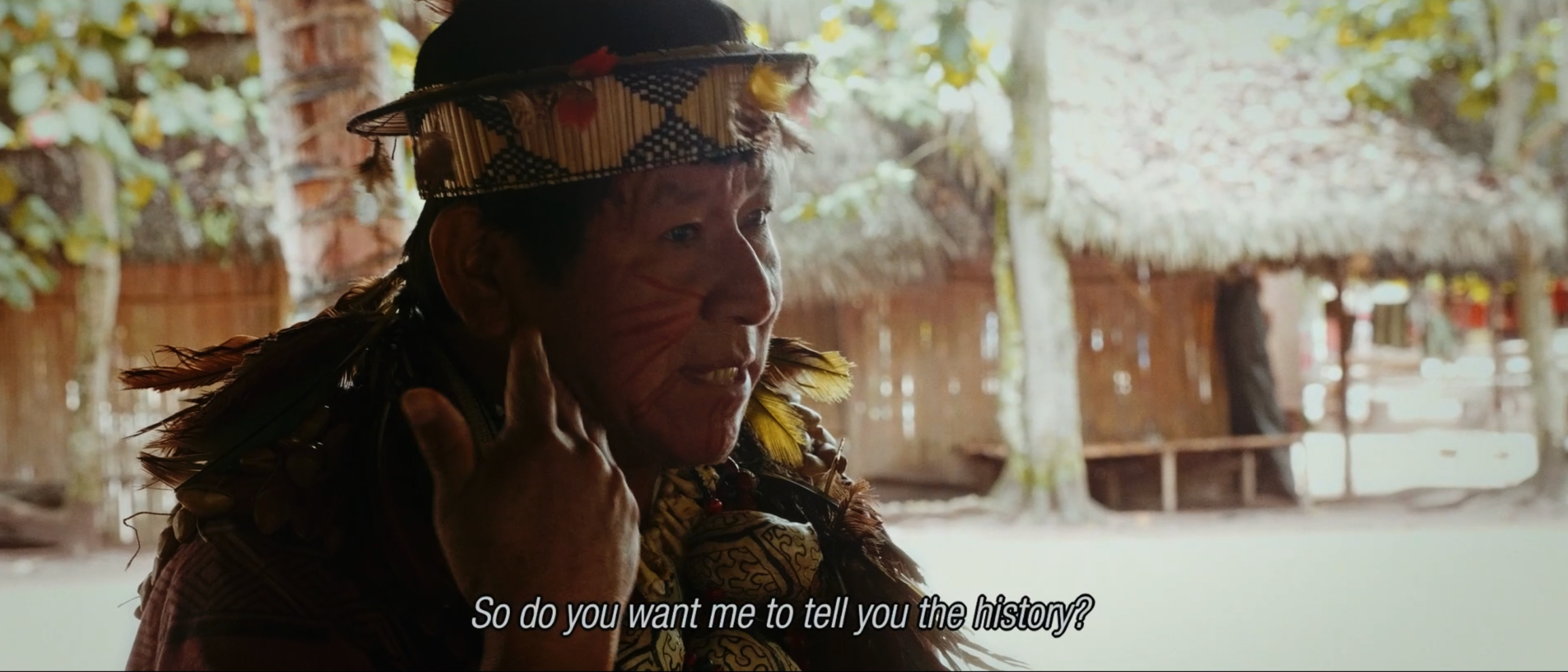

Towards the end of the 19th century, Arthur was sent by the Peruvian Corporation of London to discover fertile land for coffee plantations, and he documented his expedition in his imperial, diaristic book In Tropical Lands (1895). His mission ultimately contributed to the gross exploitation of the surrounding land and indigenous Ashéninka people.

Gee melds documentary and fiction in this film. A fictional writer named Andrew Norton acts as the stylistic voice of Iain Sinclair. Norton speaks from his home, a block of flats on the despairing Hastings seafront. Sinclair’s daughter Farne also features, doubling as Andrew’s daughter, and she travels to Peru for her father as a messenger and family representative (in reality, Iain also travelled to Peru with Farne). This level of disconnect, at once based on reality and divorced from it, gives Norton’s thoughts a dramatic staging in the film: “I stalked the treadmill corridors of future nightmares,” he says whilst pacing the claustrophobic Hastings block and considering his bloody family history. Perhaps Gee used a fictional character in order to pursue this overriding tone of solitary, introspective melodrama. Would it feel too stark and earnest if Iain Sinclair voiced these thoughts himself?

Sinclair is best known for his acclaimed London novel Downriver, released in 1991, which explores the stories of the Thames shores (think dark surrealism and Thatcher’s legacy). The book won him the James Tait Black Memorial Prize the year of its release and remains influential for its ominous, offbeat prose and its practice of psychogeography. In keeping with this, The Gold Machine is edited to give off a strong feeling of unease linked to the spaces captured. Shots from Peru include the distorted barbecued faces of the local delicacy Cuy, train journeys through mountainous landscapes, and the littered shores and areas inhabited by the Ashéninka. This looks like the footage of a disillusioned tourist and it is uncomfortable to watch through the eyes of the conflicted narrator. I think this is the intended effect.

It would be wrong to say the documentary is one-sided. The past and present are dually considered, and interviews with researchers and locals provide detail of the colonial mission to exploit the mineral-rich Peruvian land and the ensuing effects this had. We learn of the city of La Oroya which suffers from toxic lead contamination due to poor mining practices, only worsened by the shirking of responsibility by US-multinational Doe Run Peru. We also hear from the Ashéninka and their call for financial reparations. Farne presents them with copies of the original papers which show the wrongful sale of land to the Peruvian Corporation. We are left hoping that these documents prove to be the solid legal evidence needed for remediation.

Throughout these interviews and stories of damage inflicted by the global North, the voice of Norton interjects a bit too often for my taste. In these moments, a shift in mood occurs as we find ourselves back to Hastings’s haunted, introspective walls. The dark building Andrew Norton speaks from feels stuffy and tired. Is colonial guilt the sticky feeling of going nowhere? This is a question we are left to grapple with. The corridors we see Norton pace through could be a metaphor for the linear routes Arthur Sinclair and the colonisers mapped for themselves. To counteract the colonial mindset of missions and linear routes, we need to reconfigure space as expansive, generous and giving. As activism and the fight for land restitution. Gee and Sinclair would agree, however, the documentary’s stylistic gloom sometimes feels at odds with a call for action. It is a difficult but necessary task, to acknowledge dark truths whilst nourishing hopeful futures.

The Gold Machine trailer 2022 (1080p) from Hot Property Films on Vimeo.

Dartmouth Films present The Gold Machine in select cinemas from 2 September 2022.